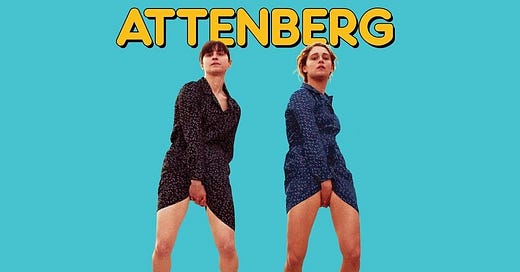

Femcel Fridays #1: "Attenberg" and "Nausicaa"

On how "Poor Things" failed to present a female gaze, Yorgos Lanthimos's penis, and the time I met Agnès Varda in Paris.

I recently went to see Poor Things at the cinema, and amidst the graphic sex with Emma Stone and shots of Mark Ruffalo’s penis, I recalled the time that Yorgos Lanthimos, the director himself, had acted in a film where he also does full frontal nudity.

The film Attenberg (2010), written and directed by Greek filmmaker Athina Rachel Tsangari, holds a special place in my cinematic memory. I first encountered it during my college days in California, a time when I was searching for movies that explored the theme of virginity in a realistic light.

"With my cinema, I don't offend women. I know that I won't cut them up into little pieces of desirable skin." — Agnès Varda

I grew weary of films like Poor Things that depicted sex in a farcical, disconnected manner. Male directors often utilized cinema to indulge in their distorted fantasies of mythical female beings devoid of any genuine romantic connection to sexuality. This frustration led me to create a curated list on Letterboxd dedicated to films that embrace the female gaze. You can find that list here.

Currently, it comprises 108 films, some of which I have yet to watch, though I am confident they meet the established criteria. These criteria include:

Female Director, Writer, or Cinematographer

At least one sex scene

I can now admit at the time I created the list, I was a sexually frustrated virgin seeking an alternative to the pervasive male gaze that saturated almost every film in the mainstream canon. My taste has evolved since then, and I no longer prioritize movies solely for their sexual content. Nonetheless, there was a period when I dedicated a significant amount of time to curating the list, drawn in by the allure of explicit scenes. Therefore, I believe it would be a worthwhile endeavor to explore this topic further and commit to writing more consistently about the films that have influenced and shaped me.

Welcome to Femcel Fridays, where every two weeks I’ll pick a few movies from my Female Gaze list, or my “Weird girls suffer more than the marines” list, and and share what they meant to me.

Attenberg begins with a provocative scene: two women engaged in an awkward kiss, their tongues tapping amidst open mouths, revealing one as the instructor and the other as the student. This bold introduction serves as our entry point into the world of protagonist Marina (played by Ariane Labed), a twenty-three-year-old woman, and her slutty, dark-haired friend Bella (played by Evangelia Randou). The film’s title is derived from Marina’s passion for watching nature documentaries featuring Sir David Attenborough, who Bella mispronounces as “Attenberg.”

“I dislike ‘quirky’ or ‘kooky,’” says Athina Rachel Tsangari, the film’s writer and director, in an interview with The Guardian. “I get really sad when I read that kind of word attached to Attenberg.”

“I didn’t want Marina to be a weirdo; I wanted her to be very solid, very dedicated to her principles, but not at ease with humans. I thought it would be interesting to observe Marina the way Attenborough observes his subjects, with a kind of scientific tenderness.”

Under an American director’s helm, Marina could easily fall into the trope of a manic pixie dream girl. Instead, the film retains a distinct Greek essence, aligning it with the “Greek Weird Wave” genre. Critics coined this term to capture the deadpan absurdity present in Tsangari’s works, as well as those of her close associate, Yorgos Lanthimos. Notably, Tsangari had a hand in producing Lanthimos's Dogtooth, further cementing her involvement in this supposed cinematic movement.

You can feel the influence of Tsangari’s work on American independent cinema, particularly Frances Ha (2012), from director Noah Baumbach and co-written with Greta Gerwig, released two years after Attenberg.

(An aside: I must admit, I never liked Frances Ha. I found it to be cheugy in a way that felt alienating, yet I didn’t fully understand why. I randomly found my answer one day in an Anna Biller tweet:

Anna Biller, of mixed heritage like myself, adeptly articulated the unsettling nature of white American indie films—they lack authenticity. They often boast about their intertextual references, mistakenly believing it enhances the significance of their work, yet they fail to innovate. The themes they explore are reminiscent of sitcoms, despite their self-proclaimed superiority, merely presented in a black-and-white format, with borrowed elements like the score from The 400 Blows to feign importance. But I digress.)

In Attenberg, the world presented feels unique without relying too heavily on technical elements; indeed, it is filmed more like a documentary. Marina navigates life in a factory town as a driver, the same factory where her father Spyros (Vangelis Mourikis) once worked as an architect. As Spyros faces a terminal illness requiring occasional MRI scans, Marina and her father find solace in each other's presence, watching nature documentaries in his hospital room.

The crux of the film revolves around Marina’s relationship with her dying father. The close world they created together is coming to an end, and he tells her she must now live alongside other people. The idea of sex scares her: “A thing inside me, moving in and out like a piston, jamming me…” grappling with her identity, she ponders if she’s asexual, despite experiencing arousal toward men. Her friend Bella characterizes Marina as “a sea urchin. You don’t let anyone touch you,” contrasting her own penchant for seeking validation through fleeting sexual encounters with strangers while working at a hotel bar.

Marina: You’re one of those women who can’t stand women.

Bella: You can’t stand them either.

Marina: Yes. But I admire them.

In a scene at Bella’s apartment, Marina admits: “I like women’s breasts. The way they bulge under blouses. I can’t take my eyes off them. It must make the women feel uncomfortable. But I don’t lust after their breasts. I admire them.” The question of Marina’s sexuality, in the hands of a lesser director, could have succumbed to a simplistic bisexual stereotype. However, when she tentatively touches her friend’s breasts in an attempt to discern her own inclinations, she finds no resonance. It’s a reminder that Marina’s sexual identity need not be confined to a specific label.

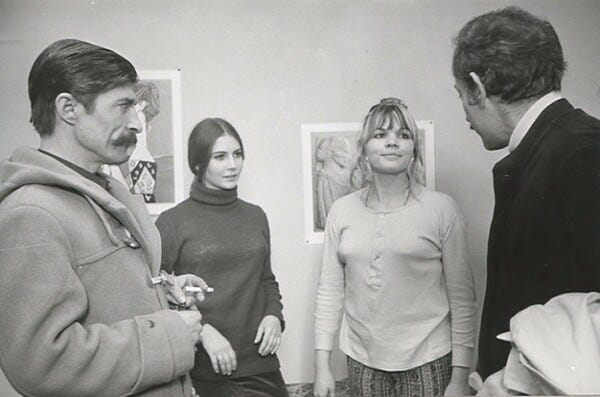

Yorgos Lanthimos’s character emerges as an engineer who, upon witnessing Marina’s contemplation of suicide by the ocean, invites her up to his room. “You like Suicide?” he says, his words carrying a double entendre, a reference to Alan Vega’s music group. Anticipating the next step (perhaps jumping ahead a few), Marina disrobes until completely nude, poised for what seems inevitable. Yet, to her pleasant surprise, Lanthimos opts not to consummate their encounter that first night; instead, he awkwardly puts her clothes back on. Their kiss marks Marina’s entrance into the realm of men beyond her father.

Marina’s recurrent visits to Lanthimos’s character at his hotel culminate in several intimate encounters, portrayed in a cinema vérité style reminiscent of Chantal Ackerman’s 1978 film Meetings of Anna (Les Rendez-vous d'Anna). It becomes apparent that Marina seeks solace in these moments of intimacy with a stranger, using them as an escape from the weight of her father’s prescient death. Marina keeps her relationship with the engineer clandestine, recognizing the likelihood of Bella pursuing him if she were to uncover their involvement.

In a poignant twist, as a final request on behalf of her dying father, Marina implores Bella to offer Spyros one last intimate encounter before his passing. Marina acknowledges that it has been years since her father has experienced such intimacy, evidenced by the remnants of his deceased wife’s belongings still adorning his office. The details of Spyros’s encounter with Bella are left to the imagination, as the narrative remains focused on Marina, with the understanding between them to never broach the subject.

When Spyros, an atheist, expresses his wish to be cremated upon his passing, it confronts a bureaucratic hurdle as the country prohibits it. Consequently, his body must be transported by plane to Hamburg, Germany for cremation. As his sole survivor, Marina shoulders the administrative burden of death, navigating paperwork and the logistics of funeral arrangements. She’s tasked with selecting the casket for his transport and later, choosing the urn for his ashes’ return. Eventually, she honors her father’s wishes by scattering his ashes into the Aegean Sea. Her father’s remorse for not adequately preparing her for a world without him looms: “I leave you in the hands of a new century without having taught you anything.”

Spyros: Especially for a country that skipped the industrial age all together. From shepherds to bulldozers, from bulldozers to mines, and from mines, straight to petit-bourgeois hysteria. We built an industrial colony on top of sheep pens and thought we were making a revolution.

Marina: I like it. It’s soothing, all this uniformity.

Spyros: Because deep down you’re an optimistic bourgeois modernist.

The candid exploration of themes surrounding sex and mortality, juxtaposed with a young woman’s coming-of-age journey through her own eccentricities, renders Attenberg a truly distinctive cinematic experience. It embraces an unapologetically unconventional narrative that may not resonate with everyone. Indeed, the presence of subtitles might deter some viewers, as was the case with my boyfriend. However, it’s precisely this unconventionality that speaks to a specific audience: femcels, or those who appreciate cinema that defies mainstream norms. In a landscape dominated by familiar tropes, Attenberg stands as a refreshing and authentic piece of cinema, deserving of recognition and appreciation.

Attenberg’s exploration of modern Greek social and political history seamlessly leads to my next recommendation: Nausicaa (1970), directed by the visionary Agnès Varda. For decades, this film was considered lost media until a rare print resurfaced in 2012 as part of the extensive 22-DVD edition “Tout(e) Varda” [ARTE ÉDITIONS], hidden within one of the bonus discs. Despite its availability for streaming on the Criterion Channel, Nausicaa remains a rare gem seldom screened, notably absent even from a 2020 film retrospective at Lincoln Center. In fact, the film was banned by the French government in 1970 after one screening. What made it so controversial?

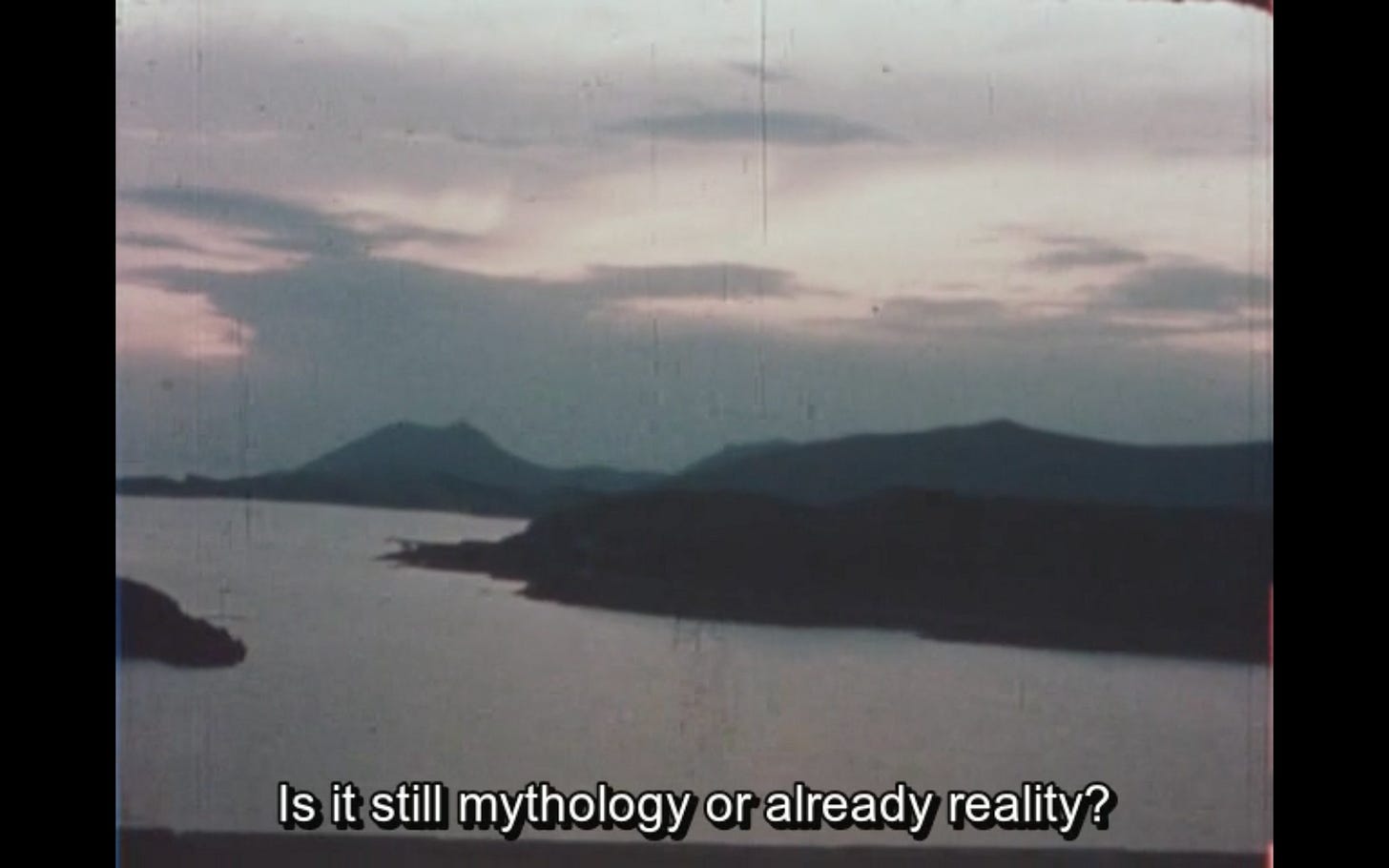

In 1970, Agnès Varda embarked on a cinematic endeavor that would transcend mere storytelling, responding to the tumultuous political landscape of Greece following the 1967 military coup. The result was Nausicaa, a film intended as a poignant gesture of solidarity with Greek refugees living in exile in France. Varda’s vision was to offer a candid portrayal of their lives, intertwining their direct-to-camera addresses with staged scenes depicting a young woman named Agnès, played by France Dougnac. This juxtaposition of real-life testimonials and fictional narrative created a multifaceted cinematic experience that resonates deeply with themes of displacement, identity, and resilience.

Despite Varda’s noble intentions, the Office de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française (ORTF), who commissioned it, declined to broadcast the film, citing political reasons. Varda revealed in a 1975 interview with Mireille Amiel that the decision was influenced by France's financial dealings with the Greek military junta. (The dictatorship was also backed the by CIA, of course).

The surviving cut of Nausicaa encapsulates three distinct films within its framework: a stirring call to arms by Greek refugees, a reflective coming-of-age story set in Paris, and an introspective essay on Varda’s own family history and heritage (her father was Greek). Despite its ban and subsequent obscurity, Nausicaa stands as a testament to Varda’s unwavering commitment to bearing witness to the human experience in all its complexity.

Nausicaa (1970) begins with raw footage featuring interviews with Greek refugees—former communists and left-wing intellectuals—who sought political asylum in Paris, France, fleeing persecution by a fascist regime that silenced dissent through torture. These interviews are unflinchingly honest, shedding light on atrocities that the French government may have preferred to keep concealed. Here's a striking example:

“One of the first things the Colonels did once they took power was to create a divorce between the popular language and the people, to put in practice the divorce between culture and people, by imposing in schools and universities a purist language. This you can relate to medieval obscurantism Byzantine, which halted the progress made in Greece towards a language we could all talk, all write and all understand.”

Another refugee recounts, “a computer was used for the arrests. The only computer we had in Greece, funnily enough. The first computer in Greece was not for production but security. It is this computer that planned the arrests.” This chilling revelation from 1970 sheds light on the grim reality of technology’s role in enabling authoritarian regimes to exert control. It’s sobering to realize how well-educated individuals spoke truth to power about a situation that still resonates today, yet remains largely overlooked. The misuse of technology for the automation of absolute control, rather than progress, is a haunting reminder of the darker implications of technological advancement. Even in France, such radical ideas were deemed too controversial for public consumption, necessitating their suppression.

This politically charged aspect of Varda’s work is less embraced by art museums and cinémathèques. She passed away in 2019 at the age of ninety, leaving behind a long, iconic legacy in cinema. In the latter half of her life, she embarked on a parallel career in the fine arts, cultivating a public persona described by Max Nelson in The Nation as, “a world full of cats, beaches, mirrors, colorful outfits, and sprouting heart-shaped potatoes.”

It was her public persona that led me to follow her on Instagram during the final years of her life. I was studying abroad in Madrid, Spain, a unique opportunity provided by my university that I managed my budget for meticulously. At twenty years old, nursing a broken heart over someone who seemed indifferent to my existence, I yearned to explore the world, hoping it might bring me solace. I adored her films, and her most recent solo art exhibition, A CINEMA SHACK: The greenhouse of Happiness, was still on display in Paris, a city I would soon be visiting for a few days.

I must have taken Xanax before, because some of it is a blur. My friend and I casually entered the fancy gallery, expecting to quickly glimpse the greenhouse exhibit and leave, as one does with art. Yet, in a surreal twist, art suddenly sprang to life. As we strolled toward the rear, I was taken aback to see Agnès Varda herself, the renowned director, seated on a couch alongside her daughter Rosalie and the French actor Louis Garrel.

I started to panic a bit, but my friend, who had no prior knowledge of the artist, remained unfazed, and stayed by my side to witness the moment. Eventually, I mustered the courage to approach Agnès. Oh, how I wish I could recall my words, flustered as I was, but she gently held my hand as I spoke. (My friend later recounted this to me.) I requested a photo, but she declined. It was rather silly of me to ask, thinking only of capturing the moment instead of simply letting it unfold.

That was really a special moment during my three months in Europe, stumbled upon entirely by chance. I felt immensely grateful to have met her, someone whose art and life were deeply meaningful to me. As a young woman, I only have the women who came before me to look up to, and meeting Agnès Varda was an affirmation of that legacy.

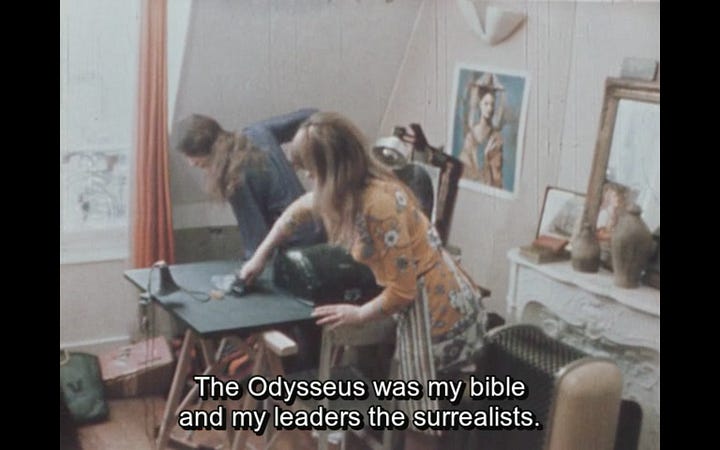

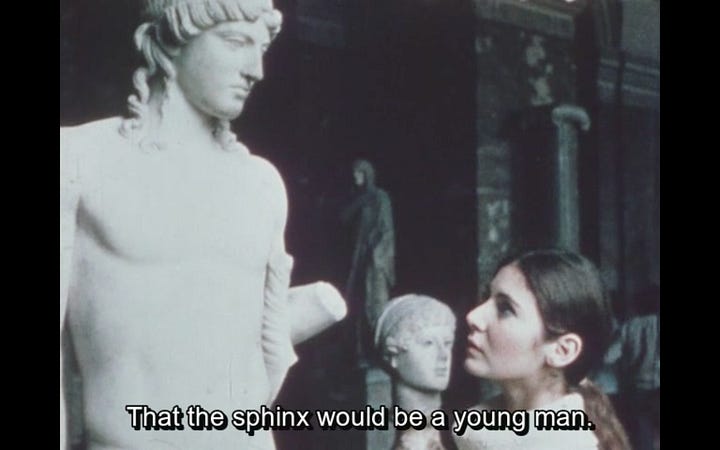

What resonates deeply with me about Nausicaa is the juxtaposition of interviews with Greek refugees alongside glimpses into Agnès’s life as a young adult. We see her self insert character studying Greek art and architecture at the Sorbonne, a period when she herself was still a virgin.

She portrays a young woman away from home, delving into the study of art as a means to unravel her own identity. Varda found inspiration in the surrealists, expressing in a voiceover:

“I was thrilled by the surrealists, I was dazzled by their insolence, their disputes, their humor, their invention. Beauty will be convulsive or it will not be. Convulsive beauty will be erotic, veiled, explosive, fixed, magical, circumstantial or it will not be.”

Seeking a deeper purpose in life, she immerses herself in Greek history, finding a personal connection to it through her father, who was born there. She engages in a sexual encounter with the Greek refugee she welcomed into her home, only to face the inevitable: he will leave her. She grapples with the stark reality that their brief liaison will not blossom into a grand love story; ultimately, it remains just that—a story.

Towards the film’s conclusion, a poignant remark is made by a political prisoner who survived torture and penned a book detailing his harrowing experiences, emphasizing the significance of sharing his narrative: “Greek fascism must be fought, in destroying the mechanism creating European fascism. It is the only help us Greeks believe in. All the rest, literature of exile, exportation heroism and international solidarity—all the rest is just cinema.”

Cinema, once thought to have intrinsic value, has lost sight of its true purpose. It should not merely be an end in itself but rather a vessel, a conduit for the human soul, waiting to be discovered by those willing to delve deeper. My mission is to gather the remnants left behind by these artists and present them to you, dear readers. For those weary of the corporate garbage force-fed to them, let's embark on this journey together and have some fun along the way. Hope to see you in two weeks. <3

Watch Attenberg for free on Kanopy using your library card. Watch Nausicaa on the Criterion Channel or from my upload.