Femcel Fridays #2: "Ms .45" and "The Self Destruction of Gia"

*Content Warning*: rape and heroin addiction. If these topics may be triggering, you may want to skip this one.

Welcome to Femcel Fridays, where every two weeks I pick a few movies from my Female Gaze list, or my “Weird girls suffer more than the marines” list, and discuss their significance.

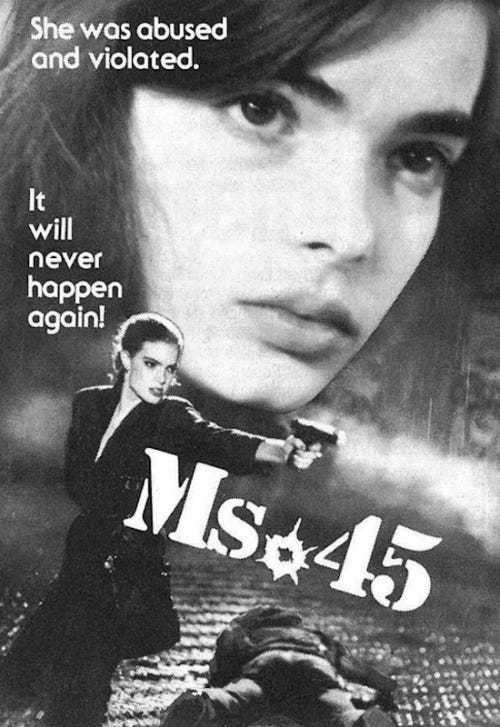

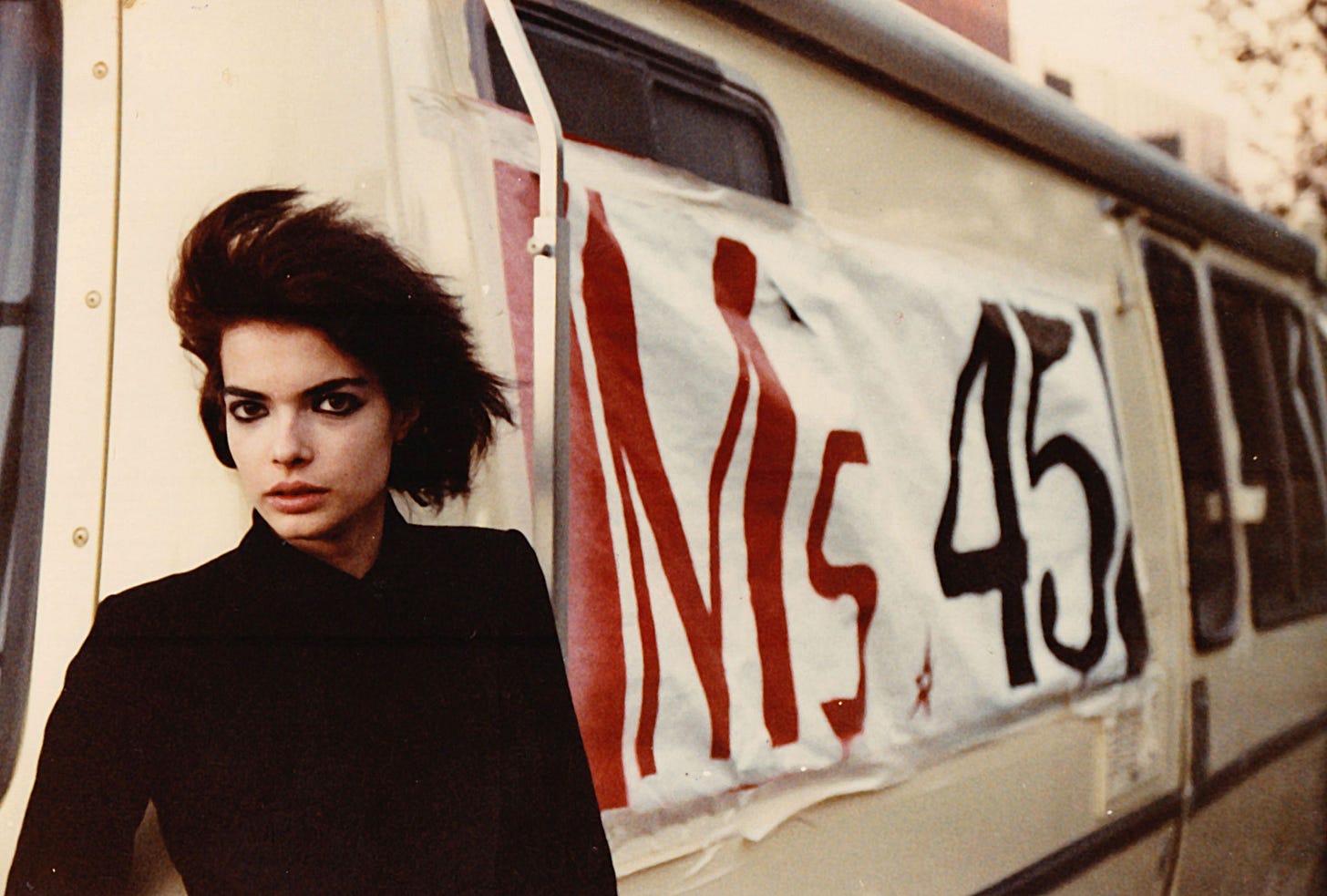

Ms .45 (1981)

Ms .45, directed by Abel Ferrara, is an underrated sexploitation, rape revenge thriller from the early 1980s. A reference to Ms .45 in HBO’s Euphoria recently put it back in the cultural consciousness, but I was captivated by the film before then. It stars actress, writer, and self-proclaimed heroin addict Zoë Lund in her first role when she was only seventeen years old.

The plot of the film is simple: Zoë Lund portrays a mute seamstress in the Garment District of Manhattan who endures the horror of being raped twice by different strangers in a single day. The second attack occurs in her home, where she is able to kill her attacker with an iron, and claim his firearm, a .45 pistol. Later, a photographer attempts to lure her to his studio under the guise of taking pictures, only to meet his demise as she swiftly shoots him with the .45 against the photoshoot backdrop. Armed with the gun, she transforms from victim to predator, the Angel of Vengeance, prepared to confront any man on the street who dares to approach her. Tragically, her empowerment leads to her own downfall: dressed as a nun at a Halloween party, she unleashes a massacre until her coworker intervenes, ending her rampage with a fatal stab. The film concludes with a haunting whisper: "sister."

Zoë Lund played a crucial role in crafting the script for Ms .45, albeit no conventional script for the film exists as the protagonist is mute. Together with Ferrara, Lund penned paragraph descriptions, a method employed the day prior to filming each scene. This spontaneous creative process imbued the film with a raw, rapid energy that mirrors the intensity of its production.

Before turning to cinema, Lund was a talented music composer, but found that cinema was a more effective art form: “I could write a concerto with 17 violins that could be very powerful, but film works on a more visceral level where I can go into the collective audience and make sure my point gets across.”1

Zoë Lund was politically minded and active from a young age. In a 1992 interview with the New York Daily News, she said, “The ultimate thing is to do something that is exciting and sexy, and within that you have the things that you want to say. The cardinal sin is to bore people.” Zoë also understood that female rebellion could serve as a potent tool for revolutionary objectives. She likened Thana from Ms .45 not only to Joan of Arc but also to Ulrike Meinhof, the German terrorist.

She loved to shit on cringe leftists before it was cool, too:

…the surface Left will spew forth an outcry in vain defense of their chaste and drug-free image. They are as bad as Nancy Reagan. These pre-terrorized “Leftists” are hopeless. No good will ever come from their quarter because anyone with courage, practical sense, or even a sense of aesthetics couldn't tolerate their company.2

As for heroin, Zoë Lund was a user for much of her life, until she died at the age of 37 in 1999. She died in Paris of heart failure from extensive cocaine use, not heroin. She wrote extensively about the benefits of safe heroin use, even submitting an op-ed to the New York Times on needle exchange programs. Reading it now, I am saddened by her enthusiasm for the drug. Like many great artists during that time in pre-Giuliani New York City, she was misguided by these drugs, believing they were the only answer to her issues:

Why do we do heroin? Once and for all, here is the answer to the “Great Mystery”: We do the drug out of some personal combination of the following - we like the way heroin feels, we love the dreams it brings on, and besides, we get damn sick if we don’t “get straight.”3

The climactic victim in Ms .45 is Thana’s boss who, in an essay, Lund likens to a rapist, not in the clinical sense but by the power he has over her financially. On the subject of rape, she writes:

The present furore over rape is the work of woman's enemy, woman. They strive to turn all women into victims. Not fighters. Not creators. Not sources. These women want their sisters relegated to the ranks of the done-to. They fear the challenge of doing.4

In the same essay she opens up about her own experience with rape, a strong voice willing to overcome physical violation: “While I was being raped, my soul was elsewhere. That man got nowhere near me. He was stuck in a hole. I was far away.”

Who wouldn't feel compelled to retaliate after enduring such brutality upon their own body? Transforming that violence into something other than more violence requires immense strength. While revolutions often entail violence, Lund herself did not advocate for it: “Woman will never free herself by tainting the tea of her oppressor, nor by shooting him in the back. She will be truly free when, like the paradigms, however ridiculous or holy, she takes hold of her own destiny, and fights for that which is larger than herself.”

Towards the climax of Ms .45, Thana’s intrusive neighbor, Mrs. Nasone, breaks into her apartment out of sheer nosiness. To her horror, she discovers the decapitated head of Thana’s initial attacker—a rapist who had invaded her home. Shocked, Mrs. Nasone condemns Thana and rats her out to the police. “She’s a horror!” says Mrs. Nasone, “She’s a witch!” No—she’s just a girl with a gun, taking back what is rightfully hers.

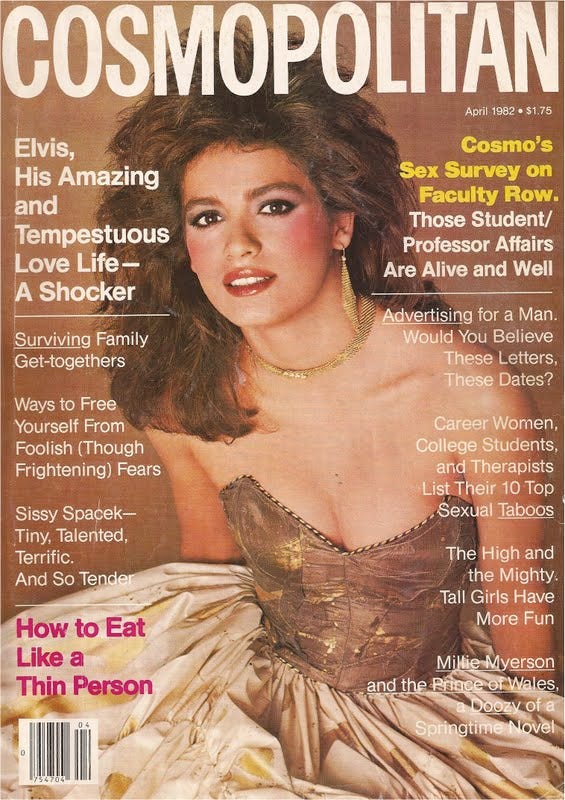

Gia (1998) and The Self Destruction of Gia (2003)

If you have yet to watch the HBO film from 1998 starring Angelina Jolie as Gia Carangi, the tragic supermodel who died of AIDS in 1986 at age 26 after struggling with a heroin addiction, I suggest starting there. The subsequent documentary The Self Destruction of Gia works best as a supplementary material (you can watch it here).

These films pair well with Ms .45 as Zoë Lund, the star of Ms .45, makes an appearance in the documentary.

I came across Gia Carangi, known as being the world’s first supermodel, via Tumblr back in high school, when I was beginning to get into cool shit I’d learned about on the web. However, admirers of Gia Carangi have existed long before my internet access, drawn to her tragic narrative, which served as the inspiration for the HBO film that solidified Angelina Jolie’s cinematic legacy. Jolie delivers an outstanding performance, skillfully capturing Gia’s essence despite the limited footage available of her.

“Fashion is not art. Fashion isn’t even culture. Fashion is advertising, and advertising is money. And for every dollar you earn, someone has to pay.” — Gia (1998)

Gia’s tale is profoundly tragic, epitomizing the dark underbelly of the fashion industry—a narrative of the quintessential all-American girl ensnared in the throes of drug abuse. Despite her struggles, agencies continued to book her, fully aware of her dependency, as they prioritized her image above all else. They exploited every ounce of her talent, even as her arms bore the scars of her addiction. “She had the best tits in the business,” says photographer Francesco Scavullo in the documentary.

“Live fast, die young, and leave a beautiful corpse”—this was the epitome of the American ethos. At one time, I too succumbed to its allure, avoiding thoughts of tomorrow by drowning myself in Xanax much like Gia drowned in copious amounts of heroin, seeking solace amidst life’s chaos. Every industry recognizes true talent when it appears, understanding its rarity and the impossibility of artificially reproducing it. Her unique, untamed beauty possessed a magnetic quality that could market anything; in her photographs, she sold not just products but also the essence of sensuality.

She pursued any beautiful woman she desired with abandon, embracing her attraction to women wholeheartedly. In the film Gia, Angelina Jolie’s portrayal captures this sentiment as she muses, “I don’t think a woman is really a woman unless she’s a blonde, you know?” In her approach to life and her desires, she mirrored the spirit of James Dean, exuding a masculine energy in her pursuit of both life and women. The concept of "heroin chic"? She epitomized it. At the height of her fame, during the Studio 54 era, she held New York in the palm of her hand.

Only someone like Angelina Jolie, so aligned in spirit with the character, could have done Gia Carangi justice on film. I can’t envision anyone else portraying the role with the same depth, especially in today’s context. People like Gia contribute immensely to the world until they exhaust themselves and burn out. However, that’s precisely why her story holds such significance—it serves as a cautionary tale for similar souls to heed, offering a chance to learn and avoid her tragic fate. I personally know individuals who have been deterred from heroin use because of this film, and that’s a positive outcome.

“The thing you have to remember is that it’s not about you…it’s not you that they’re looking at…I understand that…if you let it be about you then you’re screwed, you know? So you have to stay separate from what’s happening and you have to be somewhere else. But I don’t know where that somewhere else is, you know? Or how to do that.” —Gia (1998)

It’s a misconception that people turn to drugs and engage in dangerous behaviors because they want to die—it’s actually the opposite. The addict is driven by such a fervent desire to live that the fear of death becomes inconsequential. Gia’s former counselor disclosed that at the very least Gia had undiagnosed bipolar disorder, and there have been hints that she was sexually abused by her father as a child. If given the proper treatment, it’s possible she never would have lived the life she lived. But then we wouldn’t get those beautiful pictures! The movie they inspired! you may say. Is the cost of a human life really worth that? That is for you to decide.

I say no. Gia Carangi, Zoë Lund, these tragic, beautiful woman who used heroin to cope with the horrors of modern life—they are saints to me, beautiful American martyrs. They gave their lives fighting against the harsh reality of a world that tries to destroy beautiful people, beautiful souls. Earth is a cruel place to be born if you are anything but evil.

When I was too afraid to live in the real world, and hid behind a screen to avoid facing the outside, I lived through these women. There was something in their stories that spoke to me, something I can now go back to and recognize in myself.

I remain captivated by their stories onscreen, yet viewing these films with a fresh perspective has allowed me to glean valuable lessons—not to replicate their struggles, but to acknowledge my own experiences. Following her battle with heroin addiction, Gia aspired to lead a conventional life and dreamt of one day having children. Tragically, like many prominent figures of the era, her life was abruptly cut short by AIDS. Every organ in her body failed her, her mother vividly recounting the skin peeling off her back in her final days.

If you’re struggling with addiction, I want to assure you: it’s not too late. For the first time, I see a future with myself still in it. My story isn’t finished yet, and I hold that same hope for you.

https://zoelund.com/docs/expret/index.html

https://zoelund.com/docs/short/Narco-Terrorism.html

https://zoelund.com/docs/NeedlesOpEd.html

https://zoelund.com/filmvid/SensesOfCinema/ship.html#1